Filtering and Analyzing of Effective Packet System for ATM Network.

Effective Uses of Packet-Filtering Devices

Because packet filtering is older technology and lacks the capability to differentiate between types of network traffic, you might be wondering why we are discussing it. What could be the possible use for this technology in a world that is filled with hi-tech firewalls that can track protocols using knowledge of the way they work to intelligently differentiate between incoming and outgoing traffic streams? Good question! Why use a PC when we have supercomputers? Sometimes a lighter-weight, less expensive means to get things done is a major advantage. Because packet filters don't go to great depth in their analysis of traffic streams, they are faster than other firewall technologies. This is partially due to the speed at which the header information can be checked and partially due to the fact that packets don't have to be "decoded" to the application level for a decision to be made on them. Complex decisions are not necessary, simply a comparison of bits in a packet to bits in an ACL.

Filtering Based on Source Address: The Cisco Standard ACL

One of the things that packet-filtering technology is great for is the blocking or allowing of traffic based on the IP address of the source system. Some ways that this technology can be usefully applied are filters blocking specific hosts (blacklisting), filters allowing specific hosts (such as business partners), and in the implementation of ingress and egress filters. Any of these examples can be implemented on a Cisco router by using a "standard" access list.

The standard access list is used to specifically allow or disallow traffic from a given source IP address only. It cannot filter based on destination or port number. Because of these limitations, the standard access list is fast and should be preferred when the source address is the only criteria on which you need to filter.

The syntax for a standard access list is as follows:

Notice that when ACLs were first created, the list number had to be 1–99. This range was expanded in IOS version 12.0(1) to include the numbers 1300–1999. The only way that the Cisco IOS can identify the list as a standard ACL is if a list number in one of these two ranges is used. The mask option is a required wildcard mask, which tells the router whether this is a single host we are filtering or an entire network range. (For more information on wildcard masks, check out the sidebar "The Cisco Wildcard Mask Explained" later in this chapter). The log option can be appended to tell the router to specifically log any matches of this filter. These log entries can be saved in local memory or more appropriately sent to a remote Syslog server. For more information on router logging, see Chapter 6, "The Role of a Router," and Chapter 20, "Network Log Analysis."

The previously listed access list notation is entered in global configuration mode and can be applied to the interface in the interface configuration mode with the access-group statement, as shown here:

The access-group command is used to specifically apply an ACL to an interface (by its list number) either inbound or outbound. Only one access list can be applied in one direction (in or out) per interface. This means a maximum of two applied ACLs per interface: one inbound and one outbound.

One of the confusing concepts of router ACLs is the way that applying filters "in" or "out" works. This is confusing because people normally visualize "in" as traffic moving toward their internal network and "out" as traffic moving away from their network toward outside entities. However, this premise does not necessarily hold true when talking about the in and out keywords in Cisco router access lists. Specifically, the keywords tell the router to check the traffic moving toward (in) or away from (out) the interface listed.

In a simple dual-interface router, this concept is more easily illustrated. Let's assume you have an interface called e1 (hooked to your internal network) and an external interface called s1 (hooked up to the Internet, for example). Traffic that comes into the s1 interface moves toward your internal network, whereas traffic that goes out of the s1 interface moves toward the Internet.

So far this seems to be pretty logical, but now let's consider the internal e1 interface. Traffic that comes into e1 moves away from your internal network (toward the Internet), and traffic that goes out of e1 goes toward your internal network.

when you apply access-group commands to your interfaces that you apply the access list in the direction that the traffic is traveling, in regards to the router's interface. You might be thinking, "What is the difference, then, between inbound on the s1 interface and outbound on the e1 interface? Both refer to traffic that is moving in the same direction. Which is more appropriate to use?"

The less work the router has to do, the better. Always try to filter traffic at the first interface it enters, or apply your filters "inbound" as much as possible.

Returning to our example, if something should be blocked (or permitted, for that matter) coming in from the Internet, it would make the most sense to block it coming in to the s1 (outside) interface. In addition, if something should be filtered leaving your network, it would be best to filter it inbound on the e1(inside) interface. Basically, you should show preference to the in keyword in your access lists. Some specific exceptions to this rule exist, which involve certain access list types (such as reflexive ACLs) that require being placed outbound.

These examples often list the actual prompt for a router named "router" to remind you of the command modes that the router will be in when entering the various commands.

The following is an example of an actual filter that uses the previous syntax and 190.190.190.x as the source network's IP address that you want to deny:

This filter's list number is 11. It denies any packet with a source network address of 190.190.190 with any source host address. It is applied to the interface inbound, so it filters the traffic on the way into the router's interface.

The command to apply the access list to your serial 1 interface would be.

where we are in interface configuration mode for the interface to which we are applying the access list, in bound

Blacklisting: The Blocking of Specific Addresses

One popular use of the standard access list is the "blacklisting" of particular host networks. This means that you can block a single host or an entire network from accessing your network. The most popular reason for blocking a given address is mischief. If your intrusion detection system (IDS) shows that you are being scanned constantly by a given address, or you have found that a certain IP address seems to be constantly trying to log in to your systems, you might simply want to block it as a preventative measure.

For example, if your intranet web server should only be offering its information to your business locations in the continental United States, and you are getting a lot of hits from a range of IPs in China, you might want to consider blocking those addresses.

The blocking of address ranges is also a popular way to "band-aid" your system against an immediate threat. For example, if one of your servers was being attacked from a certain IP address, you could simply block all traffic from that host or network number. As another example, if you just found out that you had a widespread infection of a Trojan that contacted a remote IRC server, you could block all traffic coming from that IRC server. It would be more appropriate to block the traffic leaving your network to that destination, however, but that would require an extended access list because standard ACLs only filter on source address.

A sample access list to block access from an outside address range would be.

where the network number of the outside parties to be blocked would be 192.168.1.0–255. (Of course, this address range is part of the ranges reserved for private addressing, and it's simply used as an example in this instance.) This access list would be applied to the external router interface, inbound.

"Friendly Net": Allowing Specific Addresses

Another way you can use a standard access list is to permit traffic from a given IP address. However, this is not recommended. Allowing access to an address in this manner, without any kind of authentication, can make you a candidate for attacks and scans that use spoofed addresses. Because we can only filter on source address with a standard ACL, any inside device with an IP address can be accessed. Also, it's impossible to protect individual services on those devices. If you need to set up access like this and can't do it through a solution that requires authentication or some type of VPN, it is probably best to at least use an access list that considers more than the source address. We'll discuss this more in the section on extended access lists. However, this type of access may be suitable in situations requiring less security, such as access between internal network segments. For example, if Bob in accounting needs access to your intranet server segment, a standard ACL would be a simple way to allow his station access.

Ingress Filtering

RFC 1918 pertains to reserved addresses. Private/reserved addresses are ranges of IP addresses that will never be distributed for public use. This way, you can use these addresses in internal networks without worry of accidentally picking network addresses that might correspond with a public address you might want to access some day.

For example, imagine that you are in a world in which reserved private addresses don't exist. You are installing a new private network for your business that will have access to the Internet and will be running TCP/IP, so you will have to come up with a range of IP addresses for your stations. You don't want these stations to have public addressing because they won't be serving information to the Internet, and you will be accessing the Internet through a proxy server. You pick a range of IP addresses at random (say, 190.190.190.0–255). You configure your stations and set up Internet access.

Everything is working great until the first time you attempt to access your bank's website and receive an error. You call the bank, and the bank says that everything is fine on its end. You eventually come to discover that the bank is right. The bank's system you were trying to contact has a public IP address of 190.190.190.10, the same address you have configured for one of your own stations. Every time your web browser goes to send information to the bank, it never even leaves your internal network. You've been asking your CAD station for a web page, and because your CAD station doesn't run web server software, you've just been getting an error. This example paints a clearer picture of why reserved addresses are so important for the interrelationship of public and private TCP/IP networks.

The reserved ranges are as follows:

- Class A: 10.0.0.0–10.255.255.255

- Class B: 172.16.0.0–172.31.255.255

- Class C: 192.168.0.0–192.168.255.255

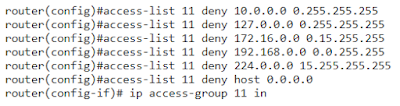

Because these ranges are often used as internal network numbers, they are good candidates for someone who is crafting packets or doing other malicious packet-transmitting behavior, including denial of service. Therefore, these ranges should be blocked at the outside of your network. In addition, the loopback address 127.0.0.1 (the default address that all IP stations use to "address" themselves) is another candidate for being blocked, for the same reason. While you are blocking invalid addresses, you should also block the multicast address range 224.0.0.0–239.255.255.255 and the invalid address 0.0.0.0. Following is a sample access list to accomplish this:

These access lists are similar to the last one, denying access to the IP address ranges listed in an inbound direction on the applied interface. Notice the host keyword when blocking 0.0.0.0 in the previous example. When blocking a single host, instead of following the IP address with the wildcard 0.0.0.0, you can precede the address with the keyword host. These lists have the same "implicit deny" that any access list does. This means that somewhere in access list number 11, a permit statement would have to exist; otherwise, all inbound traffic would be denied! An example of an appropriate permit statement might be one that allows the return of established traffic, like the following:

This is, however, an extended access list, which we'll talk more about later in the section "Filtering by Port and Destination Address: The Cisco Extended ACL."

It is also advisable that you create a rule to block traffic coming into your network that claims to have a source address matching that of your internal network, to complete your ingress access list. Valid traffic from the outside world doesn't have to have the same addressing as your stations. However, if this traffic is allowed to pass, it could bypass security mechanisms that think the traffic is local. If you are using one of the standard private address ranges, this is already done. If you're not, it would look like this:

Here, your network address range is 201.201.201.0–255. This rule would be added to the previous list before the line that allows return traffic.

Ingress filters are an excellent example of a means to use packet-filtering technology to its fullest, on any network. Even if you have a stateful or proxy firewall, why not let your perimeter router use packet filtering to strip off this unwanted traffic? Let perimeter routers be the "bouncers" of your network, stripping off the undesirables before they even reach other internal protection devices.

Comments

Post a Comment